For more than 25 years I’ve worked in the after-sales domain. Hardly ever I came across the words Digital Thread. That changed when PTC acquired ServiceMax a couple of months ago. I wish I had come across the Digital Thread concept a lot sooner. I’ve come to learn it as a powerful paradigm and being very useful in creating momentum for digital transformation. I get even more excited when I tie the ends of the thread and create an infinity loop.

What’s so compelling?

Having been a service executive for 25 year I’m rather practical and down-to-earth. I like to talk about service excellence, but my actions are more around service basics. When I hear a phrase like “data is the new oil”, I’m sceptical at first, immediately followed by curiosity.

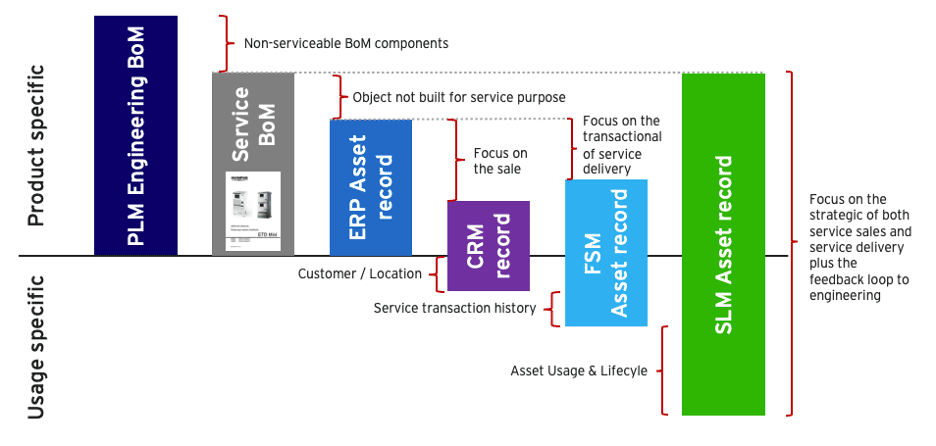

I’d like to illustrate this through a research we commissioned about the rise of “Asset and Service Data Gravity“. Though friend and foe agree on the value of data, siloed organisational design and behaviour inhibits the flow of information. Since the publication of the report in 2018, I’ve seen and heard many more stories about the value of data, but I’ve always missed the handle, the story to break the siloes.

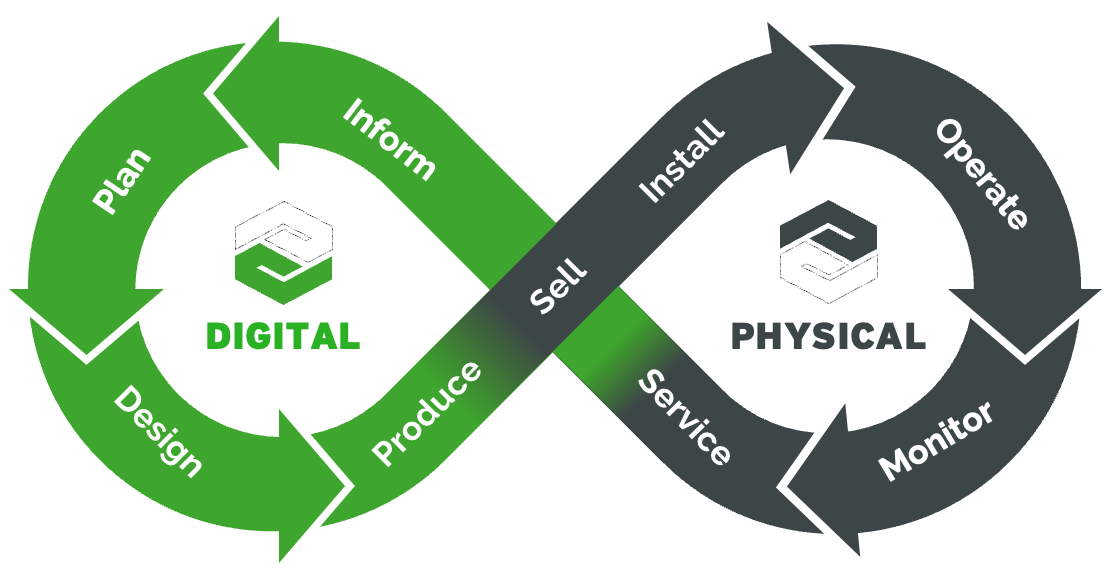

What is the ‘binding entity’ across all the business functions of an organisation? Yes, the product they sell! Some people have the idea, others design the product, next you produce it, then you sell it. Once the product goes into the ‘field’, you’ll help your customers install, operate, sustain and decommission the product. The common demeanor is the product lifecycle.

In each phase of the lifecycle the product creates data. Instead of each organisational function creating its own siloed representation of the product, you can picture a ‘thread’ where each station passes the baton onto the next. That is a compeling message for me.

Design-for-Service

One of my favourite activities in my current job is that I get to do frequent ride alongs. I ‘staple’ myself to a service request and observe each step in the process. The eye-opening part in the ride along is the ‘field’ piece. I mean the part where either the customer, technician or depot repair operator is in front of the product, tasked to fix it.

Sometimes it appears like we ask customers, technicians and operators to perform service activities ‘blindfolded’. Some examples:

- The engineering of the product is optimised for manufacturing but not for service.

- The service and operating manuals are available as reference documents, but not as actionable bite-sized instructions contextual to the job at hand.

- There is a spare parts catalogue, but finding the right part is like finding Wally. Especially when the product is a configure-to-order product.

All these bullets make it harder to service products. More effort. More cost. Less efficiency. Less margin. Lower customer experience.

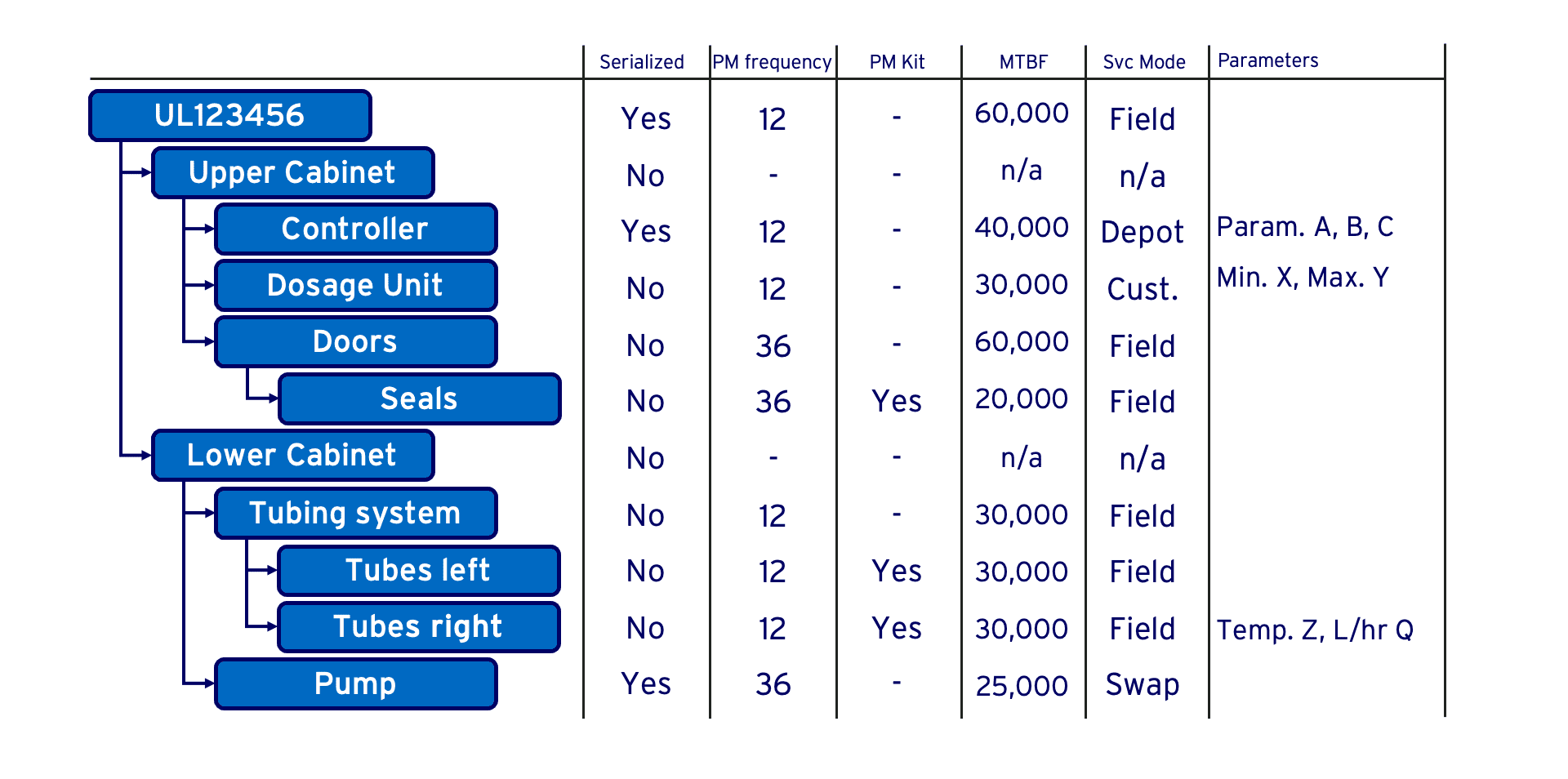

With Digital Thread we can picture an alternative future. Engineering designs a product with an intended use case in mind. Maintenance engineering ‘translates’ the product design and use case into a recommended preventive maintenance scheme, spare parts kit and component MTBF. Wouldn’t it be great if all that knowledge ‘flows’ into the after-sales and service delivery function? On the same platform?

Closing the loop

Now we have a linear thread starting with the definition of a product all the way up to sustaining and augementing the product, what would happen if we close the loop? Why is that important and who benefits?

Let me tell you a true story when I managed a field service organisation. The engineering department asked me to collect 25+ data points during the debrief of every service activity. Knowing that my technicians had not signed up for the job to do admin, I needed a lever to steer the conversation.

The good news, engineering recognised the value of data once the product was in the ‘field’. The bad, the cost of collecting the data was in after-sales/ service. To solve this dilemma, I played a game.

25 Data points equals 15 minutes admin time. Multiplied by volume. Multiplied by fully burdened cost. “Engineering, the cost of your data request is 581k per annum”. Can you guess the response? Isn’t this internal money? Endgame, engineering reviewed the list of 25+, settled on 5 questions that had an impact on value creation. Engineering funded service to collect the data. Technicians understood the reasoning of the 5 extra questions. Technicians got extra time (and pay) for retrieving the additional data points.

In all, we closed the loop, created value, balanced cost/ effort, got lasting funding and mitigated adoption. We all won.

There is more

Once engineering receives relevant and quality feedback on the performance of products in the field, you can setup a ‘plan versus actual’ process. In designing revision 1, engineering had a plan. Now the product is in the field, they receive actual. The comparison of ‘plan versus actual’ is useful in designing revision 2 of the product. This will benefit both the sale of new products as well as allow the service function to target the existing installed base with engineering and upgrade offerings.

Knowing that modern products are getting more complex and have an ever increasing digital component, establishing a closed PLM-SLM loop is critical to a sustainable and profitable business model.

Let me end with a personal note. Throughout my career it was fashionable to say “customer first”. Being in service, I deliberately voiced a counter message: “design your business processes along the axis of the product and service lifecycle”. Hence you can see why I am so enthusiastic about the Digital Thread concept and the infinity loop. For me it is a game changer.

I have no doubt why organisational siloes should, even must, work together. When you plot each organisational function on the digital thread and infinity loop, you have a simple, powerful and reinforcing visualisation. The graphic emphasises both the organisational dependencies and value amplification.

No surprise, I will repeat this message infinite times .