It’s 2010, and an OEM has asked me to blueprint their after-sales organization. I went to our sales executive and asked, “What do we tell our customers about life expectancy and maintenance costs when we sell the product?” He looked at me with a confused look.

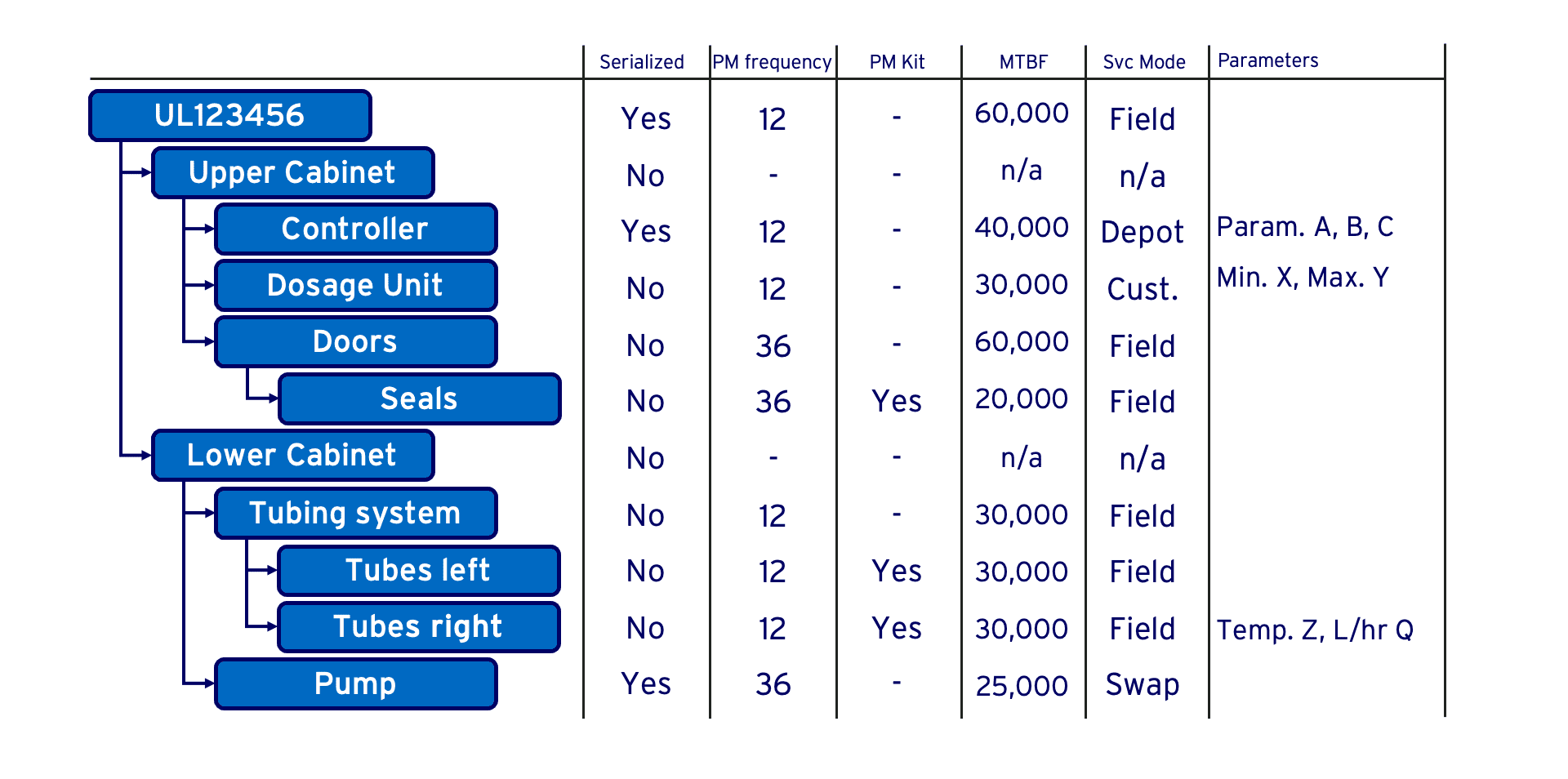

Why is this important? Because, if you want to cross-sell and upsell services in the after-sales domain, you need to know what value was promised when the product was sold. This is where the service manual and the Service Bill of Materials come into play.

This blog is part 3 in a series of three:

- Part 1 – How the Service Bill of Materials Links Engineering to Service

- Part 2 – How the Service Bill of Materials Drives System of Record Platforms

The value promise of the product sale

My sales executive sold complex capital equipment. For each product in his portfolio, engineering provided him with technical specifications describing the output capabilities. He would ask customers for their intended use profile and select the model that had a matching output bandwidth. To not complicate his CapEx sale, he would avoid a conversation on:

- How many years will the product be able to sustain specified output levels?

- What is the expected decline in output levels given the customer use profile?

- What maintenance efforts are required to sustain product specifications?

Upon delivery and title passage of the product, the buyer would have access to the operator and service manual. These provided insights into the ‘size of effort’ required to use and sustain the product. If a total cost of ownership calculation were a prerequisite to the product sale, my sales executive would defer the calculation of the OpEx piece to the after-sales department.

Total cost of ownership

I’ll skip the semantics on if we should talk about the total cost of ownership or lifecycle cost. The idea is to create an understanding of what it costs to sustain the product over a prolonged period of time while maintaining output specifications.

Once more we can draw on the intellectual property and effort from engineering. As we’ve mentioned in part 1 of this series, the service manual describes the efforts needed to maintain nominal output specifications. To put it another way for the customer, “If you maintain your product as stated in this document, we, the OEM, guarantee the output specifications.” Thus, when we cost/price those activities, we have a pretty neat approximation of the OpEx piece of TCO.

Title passage

When an OEM is in the business of CapEx sales, it will have a title passage of products. Beyond title passage, all pains and gains of the product transfer to its owner. Now it is the responsibility of the owner to act upon the instructions in the service manual. Most likely there will be a clause saying that non-compliance with these instructions ‘may’ void OEM output level guarantees. There may be a clause that voids the warranty when non-authorized parties perform maintenance activities on the product.

This is where it gets interesting and dualistic at the same time! On the one hand, the OEM bestows the risk of owning the product onto the buyer. On the other hand, the OEM wants something from the product buyer post-title passage—“buy my maintenance services.”

This happens in a context where the owner of the product has the legal right to choose to follow the user manual instructions, to ignore or deviate from them. The owner can also choose to perform the activities themselves or to outsource. If your business model is driven by title passage, you can’t force a product buyer to buy associated services. You can only entice product owners to buy your services.

Cross and upsell

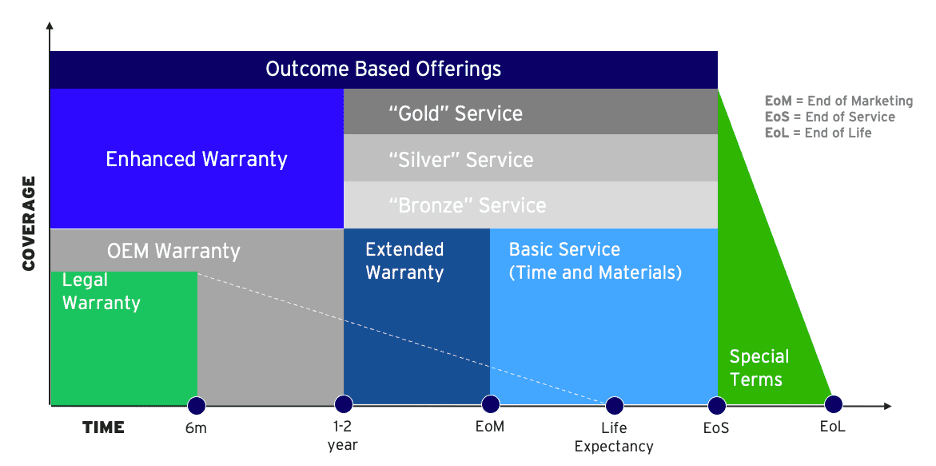

The first step to cross and upsell is establishing a baseline on what comes included with the product sale and what is extra. If the product is sold with a warranty, the warranty conditions will define what is included and what is not. It is important to clarify that a warranty is predominantly promising the correct working of the product. Not a ‘free pass’ to mitigate actual wear & tear as a result of using the product.

The second step to cross and upsell is having a conversation on how the owner will use the product. When the use is exactly as envisioned by engineering, then the operating and service manual will define the maintenance standard for sustaining the output specifications. When the customer uses the product in different settings, you may want to introduce ‘bundles’ of maintenance activities associated with low, medium, and high usage. Call them bronze, silver, or gold. For more granular services you may want to use a concept like a menu card.

Once you have jointly agreed on what maintenance activities are required to sustain output specifications given said use profile, the final step is defining who does what. This is a risk versus cost conversation. Either the product owner bears the cost and risk of using the product or those are outsourced to a service provider/OEM at an agreed price.

Companies that have a large installed base of products and trained internal technicians may choose to execute the service manual activities themselves. Others may evaluate the risk versus cost differently, and buy services ranging from preventive maintenance to full service. Mastering the risk/cost conversation in conjunction with intellectual capital captured in the Service-BoM and service manual will become your toolset for cross-selling and upselling.

Digital thread

In three blogs we’ve spotlighted the Service Bill of Materials through the lenses of cross & upsell, system of record, and linking engineering to service. We’ve seen the value of the digital thread spanning engineering, manufacturing, service, and sales—proving value across the entire product lifecycle.

This article is published on Field Service Digital.