Co-author: Katharina Streater

“It takes twice as long, at twice the cost and you will only get half of the expected functionality.” Many times, we have heard this proverbial phrase. And even if it is true, does it automatically mean you will go for the buy-variant? We’ve learned that decision-making consists of weighing many pros and cons. In this blog, we’ll provide you with a set of arguments to take into consideration.

More than just the financials (The Mindset Matters)

In our experience, a build-versus-buy decision is both multi-faceted and multi-stakeholder. To give you an example: A business leader will typically look for business process support and time to value. An IT leader may have a preference to stay on the same platform and exert control through the deployment of internal IT resources. Procurement will weigh the risk profile and continuity of the vendor base. The security officer may focus on secure, compliant transfer and storage of the business data. And finance? From finance, we expect that they will compare the cost of build versus buy in relation to the budgeting cycle.

What you have here is a mix of different personas, each with different priorities and objectives. So, how to tackle this, how to move forward? You can start to untangle this Gordian knot by genuinely trying to understand and acknowledge each stakeholder’s position.

One word of caution. However accurate the numbers are that you come up with. As you are zooming in on the pros and cons with the goal of creating a viable comparison, you need to do your homework and not only gather the facts but also be aware that each stakeholder has a different motivation.

As a business leader from Bosch said so eloquently:

“I don’t care about the make and model of the tool. I’ve got a business to run” – business leader at Bosch

We started this blog by outlining the various personas that each have their own priorities, but at the end of the day, there is one common goal: keeping the business running—today and tomorrow. And to do this, you need a solution that can either be built or bought.

What are the hidden and obvious costs?

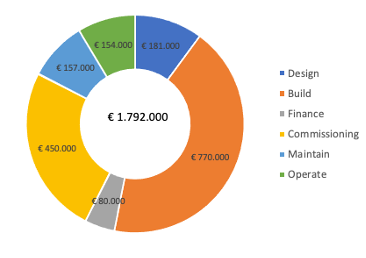

Let’s start with the most rational comparison: the financial axis. For sure the first and foremost thing finance wants to do is compare the cost of build versus buy. The purchasing cost is easy to identify. It’s the figure at the bottom of the vendor’s quotation. What is on the build side of the equation is more elusive. If building software is not your core business, it is difficult to grasp what effort goes into creating and maintaining a business application. When we see stakeholders evaluating the financials of build versus buy, typically only a fraction of the build costs turn up in the comparison. The reputed tip of the iceberg.

Together with a number of prospects, we created a model to help identify and uncover how far the iceberg extends under the waterline, in other words—to make the hidden cost elements visible. While building the model, we had to face difficult questions such as:

- How much effort does it take to retrieve the data points?

- Is it even possible to obtain an insight into the below-sea-level items?

- To what extent will a complete view of the build cost influence the decision-making?

In close collaboration, we discovered two findings:

- Apart from any numeric comparison, getting a complete picture of all cost elements proved to be extremely insightful and changed how both scenarios are evaluated.

- Appraising the ‘submerged’ cost elements is essential in defining the tipping point.

Evaluating build versus buy

When making a build-versus-buy decision business leaders strive to get a complete picture of the cost aspects and understand the impact on the business as a whole. But how do they know that? This is where the iceberg comes into play.

When working with prospects and customers to uncover the true cost for them, we found the iceberg to be an educational exercise and a great conversational framework to understand all aspects of business application creation and usage. Different areas in the framework have different owners and they don’t all have the same agenda, e.g. the cost for software developers falls within the IT department, whereas cloud-subscription fees come out of the line of business budget.

Our framework requires input from all areas that DIY touches on. By doing so, it also reveals the mindset and priorities of the different stakeholders and provides insight into the evaluation criteria of the build-versus-buy decision. As such it will be an eye-opener and helps to align all stakeholders.

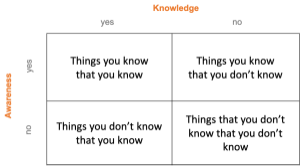

Conscious Competence Learning Matrix

‘Hidden’ costs impact the tipping point

The hidden or underwater costs play a significant role in determining the tipping point. It’s a matter of simple mathematics. The more you can exclude hidden costs from the equation, the more your decision will lean towards build. This conclusion led us to investigate why one would exclude hidden costs. We found:

- The effort to retrieve the hidden cost is too high.

What to do about it: This is fairly easy to mitigate. To find your way out of this impasse, think about using estimates and guesstimates as an alternative to actuals. As long as your data is ‘good enough’, you can still use it to make good decisions. Thus, not creating an exact cost comparison, but a probable comparison.

- We don’t want to include hidden costs.

What to do about it: This finding is more of a political and commercial nature. Here it matters who you are talking to. You can imagine that a sales rep who is trying to sell the buy-scenario has an avid interest in having as many costs associated with the build-scenario and vice versa. To overcome this potential conflict of interest, we co-developed the cost comparison model. As a result, we know that all cost elements in the model are relevant to the decision-making. When we encounter a persona saying that a particular cost element is non-retrievable, we have solid arguments to go into challenger mode.

A blend of arguments

We started this blog by explaining that a build-versus-buy decision spans multiple departments and stakeholders, and we gave the financial aspect the most weight when it comes to making the choice. There are certainly other factors that play a role in the decision, such as time to value, feature richness and risk, but ultimately, all of these aspects affect the total cost to build.

For several of our prospects, the co-developed framework has been instrumental in finding an answer when faced with the question Do I Build or Do I Buy?

If you want to find out what other aspects are influencing the build-versus-buy decision, check out our Build-Versus-Buy Guide here.

This article is published in ServiceMax Field Service Digital on June 22nd, 2021